Governance refers to the overall direction and oversight of an organisation. In the private sector, the governing body is the board, and they set strategy and provide oversight. The management team are responsible for implementing the strategy and reporting back to the board. So there are two layers:

- Governance (sets strategy and provides oversight)

- Management (implements strategy)

In local government the municipal council is the governing body, and they are supported by the municipal management team. In the public service the distinction is not so clear because there is no overarching governing body. To an extent one can say that the Executive Authority is the governing body (as they are responsible for strategy and oversight). In reality, however, it is EXCO that fulfils many of the governance responsibilities.

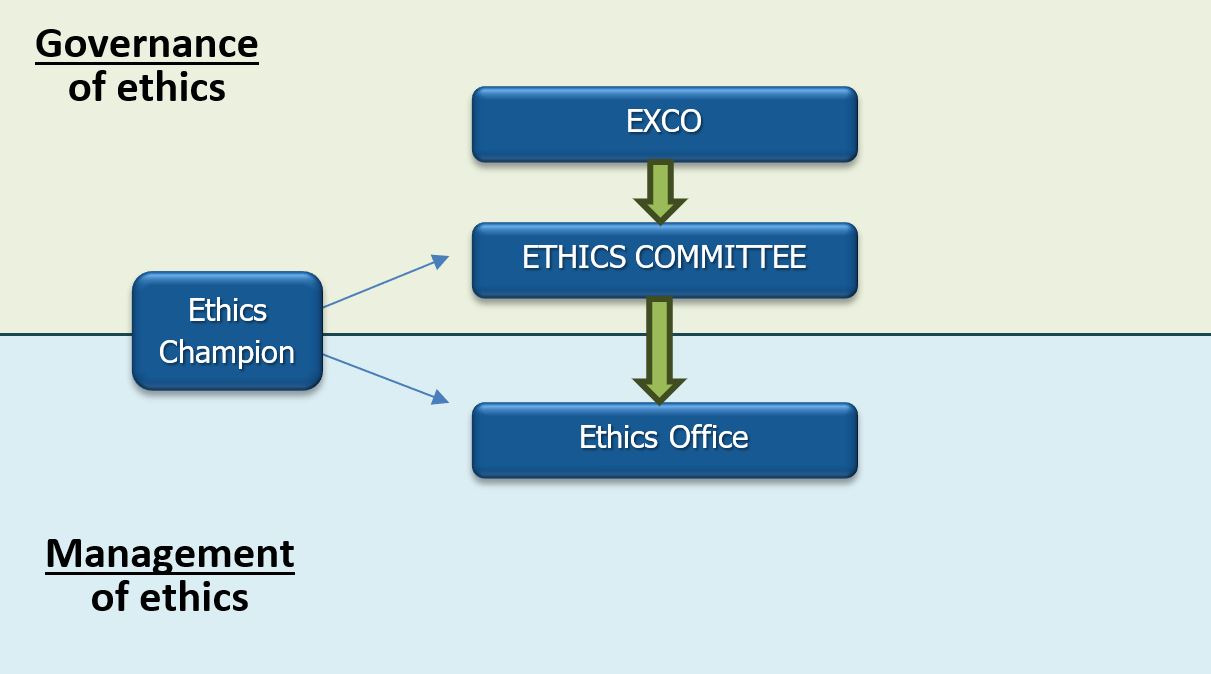

In ethics management there should also be both governance and management functions.

The picture below reflects the distinction between the governance of ethics and the management of ethics. We will unpack this distinction by looking at what these entail and the relevant role-players.

Source: The Ethics Institute

Main Resources

While we give a brief overview of ethics committees here, we suggest that ethics officers acquire a more comprehensive understanding by also reading the following:

- Public Service: Ethics Committee Guide (DPSA, 2019)

- Public Service: Ethics Committee Charter Template (DPSA, 2025)

- Local Government: Local Government Ethics Committee Guidebook

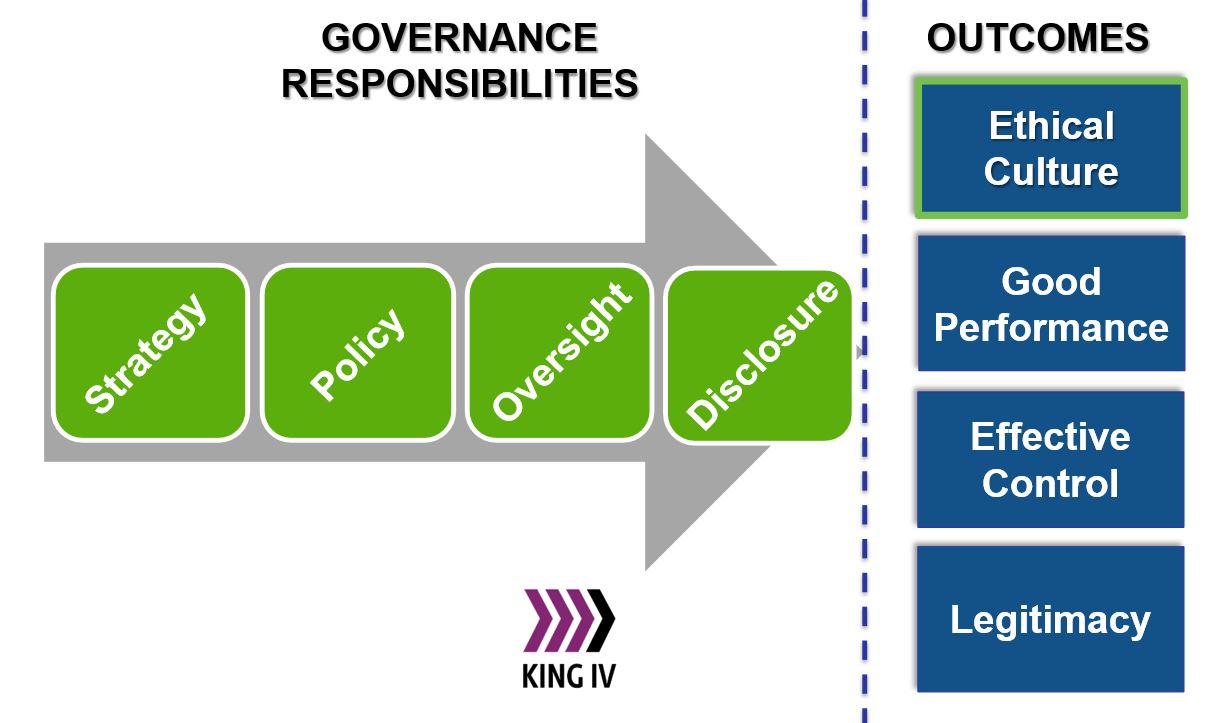

The governance of ethics is what happens above the line. This is what is captured in Principle 2 of King IV, which states that: “The governing body should govern the ethics of the organisation in a way that supports the establishment of an ethical culture” (IoDSA, 2016).

In line with Principle 2 of King IV, there should be an appropriate governance committee whose role it is to exercise oversight over the organisation’s ethics management programme. This would typically be done by an ethics oversight committee.

The role of the ethics oversight committee is to govern the ethics performance of the organisation to support the building of an ethical culture.

Essentially, this committee must set a strategy for ethics, approve ethics-related policies, exercise oversight over the implementation of the ethics strategy and policies, and disclose how the strategy is being implemented. This should be done towards the outcome of an ethical culture.

In King IV, ethical culture is an outcome of good governance. This means that ethics must be governed in such a way that over time, people in the organisation think, act and behave in an ethical manner. Culture is defined as “the way we do things around here”. Ethical culture means that the way we do things here is ethical; we think, act, behave and respond in an ethical manner and it is easy to do the right thing in this environment.

Public Service

For public service departments, the requirements for an ethics committee can be found in the Public Service Regulations, 2016 as amended, which provide in section 23(2) that the Head of Department shall establish an ethics committee or designate an existing committee, chaired by a member of the SMS, preferably a Deputy Director-General, to provide oversight on ethics management in the department.

The Public Sector Ethics Committee Guide developed by the DPSA is a useful guide for public service departments on the functioning of ethics committees.

The ethics committee is mandated to provide strategic direction and to perform oversight on ethics management in the department by setting the strategy for ethics, approving ethics policies, exercising oversight and reporting.

Members of the ethics committee may consist of representatives from various units in the department such as:

- Ethics office

- Risk management

- Human Resource (including labour relations)

- Investigations

- Legal

- Communications

- Governance, etc.

The DPSA guide sets out that the ethics committee has delegated authority from EXCO to:

- Provide oversight and support to the custodians of the ethics and anti-corruption programme

- Meet regularly to assess the strategic plan and direction of the programme

- Mobilise resources for the implementation of the ethics and anti-corruption programme

- Communicate ethics and anti-corruption messages to the rest of the staff

- Take resolution of an instance of violation of the ethics policy, including possible recommendation of sanctions to labour relations

- Elaborate further on policies regarding ethical standards of the department

- Take possible remedial actions due to deficiencies in ethical standards

- Amend the ethics policy when necessary

- The Chair of the Committee shall consult on a regular basis with the EXCO and the chair(s) of other committees of the department to ensure consistent application of the ethics policies across the governance processes.

The ethics committee therefore has a dual role: on the one hand it is to coordinate and take action if necessary, and on the other hand it is also to provide oversight over the ethics programme.

It is important for an ethics committee to have clear terms of reference which spell out its roles and responsibilities as well as accountability lines.

The ethics office would report to the ethics committee. Generally, the ethics committee would be chaired by an ethics champion and the ethics office would be the secretariat as well as provide reports to the ethics committee on its activities in driving the ethics programme.

Local Government

For municipalities, the requirement for an ethics committee can be found in the Municipal Integrity Management Framework.

| Municipal Integrity Management Framework – Principle 3

3. Governance structures and capacity: Appropriate governance structures must be in place and should ensure effective governance, oversight, and the implementation of the integrity management framework. There should be sufficient capacity to implement the integrity management framework. |

This principle draws a very strong distinction between the oversight or governance of a municipality’s ethics/integrity initiatives by Council and the management or implementation of a municipality’s ethics/integrity initiatives by the municipal administration.

This principle is further fleshed out in the MIMF as follows:

| Municipal Integrity Management Framework, 2016

Principle Three: Governance Structures and Capacity 1. Oversight committees a) Each municipality must establish an Audit Committee (in line with the MFMA s.166), which must be effective in fulfilling its mandate. b) Municipalities should also consider establishing the following committees (in line with section 79 of the Municipal Structures Act as amended):

Note: The 2021 Amendments to the Municipal Structures Act now provide for the establishment of MPAC in terms of s79A (new provision). 2. Oversight of allegations and outcomes a) The municipal council must provide oversight of allegations and outcomes as set out in the MFMA: Municipal Regulations on Financial Misconduct Procedures and Criminal Proceedings (2014). Note: The Regulation refers to this body as a Disciplinary Board. 3. Oversight of the anti-corruption/integrity management programme a) A relevant committee (such as the Municipal Public Accounts Committee) should provide strategic guidance and oversee implementation of the municipality’s integrity promotion and anti-corruption strategy. Note: We refer to this as a Council Ethics/Integrity Oversight Committee.

|

The picture below reflects the governance structures described in the Municipal Integrity Management Framework.

The Local Government Ethics Committee Guidebook explains the link between these committees.

The role of the council ethics oversight committee is to:

Provide strategic guidance and oversee the implementation of the municipality’s integrity promotion and anti-corruption strategy.

Continuously monitor progress with the implementation of the strategy.

In instances where there is lack of implementation, there should be a response. This could include improved support and resources or holding non-performing officials accountable.

Whilst not provided for in the Municipal Integrity Management Framework, for practical reasons, municipalities are encouraged to establish an operational Ethics Working Group within the administration as good practice.

The primary purpose of this working group is to facilitate better coordination and integration of ethics initiatives in the municipality. It will also ensure support for the implementation of the municipality’s ethics programme. The working group creates a platform for alignment on ethics goals and initiatives across the various role-players in the municipality who are responsible for implementing the ethics programme. (In the public service, there is no need for a working group as the ethics committee serves as both an oversight committee as well as a coordinating structure.)

The working group should have a Terms of Reference which clearly sets out its responsibilities.

Key responsibilities of Ethics Working Group:

|

Given its coordination role, the Ethics/Integrity Working Group should ideally be a multi-disciplinary group which is chaired by the Integrity Champion. The working group members should ideally be the executive directors or heads representing the diverse units across the municipality. The following are some of the key departments who could form part of the Ethics Working Group: Ethics Office, HR, Legal, Risk, Municipal Manager’s Office, Communication, and Speaker’s Office.

Following the discussions at the working group meeting, the ethics officer would be able to provide a consolidated picture to the Ethics Committee in terms of what is being done by various role-players across the municipalities to implement the ethics programme.

Ideally, the Ethics/Integrity Working Group should be a dedicated working group whose focus is solely on ethics management, coordination, and integration. It should meet quarterly and ad hoc when necessary. Should it not be practically possible to have a dedicated Ethics/Integrity Working Group, it may also form part of an existing operational committee within the administration. It is, however, important to ensure that sufficient time is allocated for the discussions around the coordination and integration of ethics initiatives.

Other Resources

General Resources

Public Service Resources

Local Government Resources

- Municipal Integrity Management Framework (which forms part of the Local Government Anti-Corruption Strategy)

- TEI’s Local Government Ethics Committee Guidebook

The ethics champion is a person at executive level who advocates or champions for the ethics management programme at the executive level of the organisation. This is not a formal role. The ethics champion is a figurehead for championing the ethics programme.

Typically, a member of EXCO would be designated to be the ethics champion. This means that they are assigned the role within their existing employment. They are not formally appointed into the role.

The ethics champion is the person who advocates for the ethics programme at EXCO and reports on the ethics programme to EXCO, as well as to the ethics committee. The ethics champion is therefore the link between the governance of ethics and the management of ethics.

The ethics champion role includes:

- Providing the vision and energy required to launch/ drive the ethics programme

- Marketing ethics in the organisation

- Ensuring that ethics initiatives gain and retain prominence

- Ensuring that the ethics management function is adequately resourced

- Guiding, mentoring and leading the ethics office

- Strategically guiding the spread/ reach of the ethics management functions

Resource

TEI’s Ethics Office Handbook

Governance refers to the overall direction and oversight of an organisation. In the private sector, the governing body is the board, and they set strategy and provide oversight. The management team are responsible for implementing the strategy and reporting back to the board. So there are two layers:

- Governance (sets strategy and provides oversight)

- Management (implements strategy)

In local government the municipal council is the governing body, and they are supported by the municipal management team. In the public service the distinction is not so clear because there is no overarching governing body. To an extent one can say that the Executive Authority is the governing body (as they are responsible for strategy and oversight). In reality, however, it is EXCO that fulfils many of the governance responsibilities.

In ethics management there should also be both governance and management functions.

The picture below reflects the distinction between the governance of ethics and the management of ethics. We will unpack this distinction by looking at what these entail and the relevant role-players.

Who is an ethics champion in the public sector?

The term ethics champion in the public sector was first introduced in the Minimum Anti-Corruption Capacity Requirements, which called for the appointment of an “ethics champion” in departments who is responsible to drive ethics and anti-corruption initiatives. It should be pointed out that ethics champions are not required by regulations. It is, however, strongly suggested as best practice.

An ethics champion is a well-respected member of top management (or a person who functions close to them) who visibly embodies the department’s ethics drive. ‘Ownership’ of the ethics drive is given to them by top management, and they then ensure that the ethics and anti-corruption initiative retains its momentum – and that all the different anti-corruption actions in different parts of the organisation are properly integrated.

An ethics champion should be someone with an intimate knowledge of the organisation’s business, culture and activities. It should also be someone of high legitimacy and credibility – ideally someone who has facilitated similar initiatives in the past.

So, in short, an ethics champion is a very senior person in a department who strongly advocates and drives the ethics cause in that department. The role includes:

- Driving the department’s ethics management programme and ensuring that it retains momentum;

- Chairing the ethics committee (where appropriate);

- Ensuring the coordination and integration of the department’s ethics initiative with other related initiatives (such as anti-corruption, policy development, compliance, risk management, and service delivery plans);

- Ensuring procedures are in place to investigate misconduct; and

- Elevating significant ethics issues to the HoD.

While an ethics champion is not formally required, the sentiment was carried into the Public Service Regulations, 2016 as amended, which provides that the ethics committee should be chaired by someone senior such as a DDG or Chief Director, who would report to EXCO. It makes sense that the chair of the ethics committee and the ethics champion be the same person if possible.

Whilst not a formal position, it is important that the ethics champion should be someone who is credible and trustworthy, as they are seen as an ethics role model in the organisation.

Who is an ethics champion in local government?

The Municipal Integrity Management Framework provides guidance as to who an ethics champion is in a municipal context.

| MIMF Principle Three: Governance Structures

3.4. Integrity Champion A member of the senior management team should be assigned the responsibility to champion the integrity management initiatives of the municipality. |

In a municipality, the integrity champion would ideally be a member of the municipality’s senior management team (s56 manager) who has been assigned the responsibility by the municipal manager to advocate for, and champion the municipality’s integrity management initiatives. This would typically be the senior manager in whose unit or domain the ethics office has been placed.

The integrity champion is not a full-time dedicated function. This person takes on the role of the integrity champion and conducts this role in addition to their primary role in the municipality.

The ethics champion provides guidance and leadership to the ethics office and is the link between the ethics office and the ethics governance structure.

Within the organisation, there needs to be a unit which is responsible for managing the ethics programme. This is typically called the ethics office.

The ethics office is a dedicated internal function responsible for the implementation of the organisation’s ethics management programme. The ethics office drives the organisation’s ethics programme and ensures that ethics is integrated into the organisation. It is responsible for the design, implementation and management of the ethics management programme which is informed by the ethics strategy.

The responsibility of the ethics office is to:

- Promote ethics and integrity in the department;

- Advise employees on ethical matters;

- Identify and report unethical behaviour and corrupt activities to the Head of Department;

- Manage conflicts of interest, including:

- Financial disclosures of employees;

- Lifestyle audits;

- Application for other remunerative work;

- Gifts and hospitality.

- Develop and implement awareness programmes; and

- Keep a register of all employees under investigation and those disciplined for unethical conduct.

The work of the ethics office is typically split into:

- Culture work – work that is aimed at proactively building the ethical culture of the organisation; and

- Compliance work – work that is in compliance of regulatory requirements, such as managing conflicts of interest.

Organisations vary in terms of having an ethics office. Some organisations have a dedicated ethics office, while smaller organisations may have ethics integrated into the function of other units.

In 2024, the DPSA issued the Directive on the Institutionalisation of the Ethics Officer Function in the Public Service to guide public service departments on how to create an environment that would be supportive of an ethics function. It includes guidelines, as set out in the table below, to help departments determine what kind of ethics and integrity capacity should be put in place.

To better understand the table, it is useful to know the distinction between appointed and designated ethics officers.

Given that departments have different capacity and resources, in smaller departments which may not be able to afford to appoint a full-time ethics officer or where the ethics risk profile is low, the Executive Authority may designate employees to perform the ethics function temporarily. This would be done in addition to the functions which these employees have been carrying out in terms of their existing posts. (It must be emphasised that even in such cases, the responsibilities cannot be assigned to someone without adding it to their key performance areas (KPAs). In other words, if you are designated to do the work of the ethics officer, this should be reflected in your KPAs.)

In cases where the ethics risk profile is high, or the context is such that ethics is a serious issue of concern and the department has the capacity and resources, it may be prudent to rather appoint a dedicated ethics officer whose role would be to focus completely on the ethics programme in the department.

| Description of size of department | Value of annual goods & service plus capital budget (R million) | Total number of employees (headcount) | Guideline in terms of internal anti-corruption, ethics & integrity capacity to be established |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Typically, a goods and services + capital budget of less than R1,000,000,000 | Typically, less than 1 000 employees | Designate at least 1 official to perform the ethics, integrity and anti-corruption functions on an add-on basis.

If, despite its small size, a department has a high aggregate risk profile and the workload justifies this, then a full-time official can be appointed to perform the ethics, integrity and anti-corruption functions and/or (an) existing unit can be assigned these functions. |

| Medium | Typically, a goods and services + capital budget of between R1,000,000,000 – R5,000,000,000 | Typically, between 1 000 – 10 000 employees | Designate the ethics, integrity and anti-corruption functions to one or more officials on a full-time basis or two or more officials on an add-on basis.

The decision whether or not to appoint officials on a full-time basis would depend on the risk profile of the department and the workload attached to these functions. |

| Large | Typically, a goods and services + capital budget of over R5,000,000,000 | Typically, over 10 000 employees | Create (a) unit/s or assign to (an) existing unit/s the ethics, integrity and anti-corruption functions, including two or more full-time officials who can perform these EO functions – the number of units and officials required to be informed by e.g. level of centralisation/decentralisation of the department, its risk profile and the workload. |

Table: Guidance on ethics capacity per organisational size

Given that every public service department is unique with its own budget and capacity, it is within the powers of the Executive Authority of the department to structure the department.

In terms of the location of the ethics office, generally, ethics, integrity and anti-corruption functions are located within administration/support functions of departments.

Ethics officers

The ethics office is staffed by ethics officers. The ethics officer function has been included in the 2024 Public Service Occupational Dictionary as a distinct occupation, and defined as “Promotes and implements code of conduct, including anti-corruption, ethics and integrity management”.

As such, Regulation 23 of the Public Service Regulations, 2016 provides that:

| 23 (1) An Executive Authority shall designate or appoint such number of ethics officers as may be appropriate, for the department to: | |

| a) promote integrity and ethical behaviour in the department; | Culture work |

| b) advise employees on ethical matters; | |

| c) identify and report unethical behaviour and corrupt activities to the Head of Department; | Detection |

| d) manage the financial disclosure system; and | Compliance work |

| e) manage the processes and systems relating to remunerative work performed by employees outside their employment in the relevant department. |

For purposes of clarity, we have divided the work of the ethics officer into three categories which will be used throughout this guide:

- Culture work;

- Compliance work; and

- Detection.

Local Government

The Municipal Integrity Management Framework (MIMF) sets out all the work that has to be done to manage ethics and prevent corruption in a municipality, but it is less clear about who has to do the work. This is because there are many small municipalities who may not be in a position to appoint a full-time ethics officer. The MIMF therefore sets out the following:

| Municipal Integrity Management Framework (2015)

MIMF Principle Three: Governance Structures 3.5. Integrity Management Capacity a) An official or unit should be delegated the responsibility for coordinating or implementing the municipality’s integrity management initiatives. |

We therefore recommend that municipalities use the guidance provided to the public service on setting up ethics offices.

In practice, it is found that the work of ethics officers is frequently conducted by risk managers in local government.

It should also be pointed out that the work of ethics officers in local government is not to manage the ethics of councillors. That is the work of the Speaker. Ethics officers’ focus will remain on municipal staff members.

Strategic Work

Strategic work is done once in 3 years. This work integrates ethics into the organisation’s long-term vision, governance systems, decision making, and stakeholder engagement.

Institutionalisation

Everyday Work

The institutionalisation of ethics is the core role of the ethics officer or the everyday work. The focus of institutionalisation is on how to make ethics real in the organisation so that it becomes part of the organisational culture.

INSTITUTIONALISATION

Making Ethics RealIn The Organisation.

The work of the ethics officer is to manage the ethics programme of the organisation.